How a State Strips an AI of Its Ethics

AI as a Weapon: Assessment, Pentagon Crisis, and Consequences

February 25, 2026

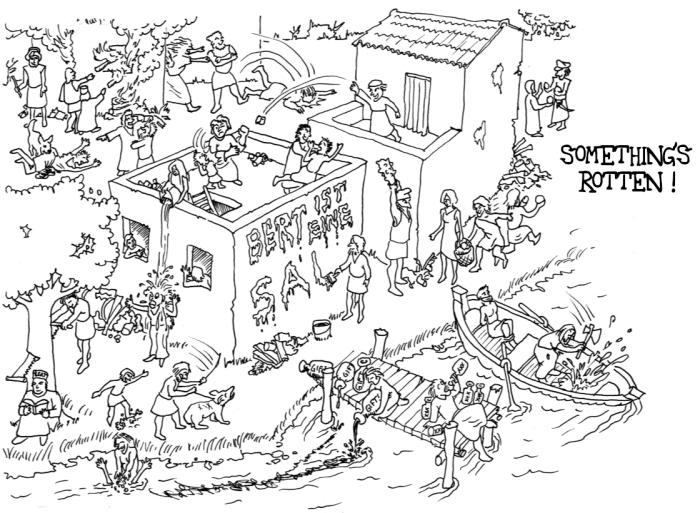

What was once considered science fiction is now reality. Artificial intelligence is already the most powerful dual-use tool in human history: useful and destructive in the same breath. As this text is being written, an ultimatum from the U.S. Department of Defense against Anthropic is counting down — an ultimatum that puts far more at stake than a $200 million contract. The question at the heart of it is whether democratically legitimized ethical boundaries can still hold against the logic of state power.

I. Taking Stock: How AI Is Already Being Misused

The systematic misappropriation of AI systems operates on three levels: state, criminal, and military. They interlock, reinforce each other, and create a reality that began long before the Pentagon ultimatum.

State Surveillance and Repression

China operates the world’s most advanced AI-powered surveillance regime with its Social Credit System. Facial recognition, behavioral analysis, and real-time movement profiles enable seamless monitoring of 1.4 billion people. Xinjiang is the laboratory: Uyghurs are categorized, tracked, and funneled into camps by AI systems. Similar technologies — often Chinese exports — can be found in Ethiopia, Iran, Venezuela, and Belarus. AI makes repression scalable. What once required armies of intelligence agents is now handled by an algorithm.

Western democracies are not immune. British police deploy facial recognition in public spaces; U.S. law enforcement agencies use AI prediction tools whose discriminatory potential has been documented repeatedly. The boundary between security and control is a political one, not a technical one.

Military Decision-Making Systems

Israel deploys the Lavender system in the Gaza war — an AI program that identifies targets for airstrikes. According to reports, thousands of targets have been generated through algorithmic classification with minimal human review. The U.S. uses AI assistance systems in drone operations — and not only in theory: during the operation against Nicolás Maduro in Caracas on January 3, 2026, Claude was deployed via Anthropic’s partnership with defense contractor Palantir. The result: 83 dead, including 47 Venezuelan soldiers. Anthropic knew nothing about it. When an employee followed up to ask whether Claude had been used in the operation, this simple inquiry triggered alarm at the Pentagon — and was treated as evidence of Anthropic’s supposed unreliability. It was not the unauthorized deployment of an AI in a lethal military operation that outraged the Pentagon — it was the question. The pattern is clear: AI is steadily taking over decision-making functions in life-and-death situations, while accountability and human oversight systematically erode.

The Criminal AI Economy

On platforms like HuggingFace, over 8,000 modified models exist whose safety mechanisms have been deliberately removed — so-called “uncensored” or “abliterated” models. Tools like WormGPT, FraudGPT, and OnionGPT are rented out as subscription services on dark web marketplaces. They enable tailored phishing campaigns, social engineering attacks, child sexual abuse material, and the planning of physical violence. This parallel economy has long since ceased to depend on Claude, GPT-4, or Gemini — it draws on open weights that no one can take back.

II. Hegseth’s Offensive: Scope and Legal Limits

The Pentagon ultimatum of February 25, 2026 is historically blunt. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth demanded that Anthropic lift Claude’s ethical restrictions for all “lawful military purposes” by Friday at 5:01 p.m. — or face contract termination, classification as a supply chain risk, and activation of the Defense Production Act (DPA). What Hegseth and other administration officials mean by this was made unmistakably clear: Anthropic’s refusal to release AI for autonomous weapons systems and mass surveillance was labeled “woke AI” — a politically charged term used in the Trump administration as a catchphrase to discredit any safety mechanisms on AI systems. AI experts note that “woke AI” is a deliberately vague term that effectively subjects all ethical limits to blanket suspicion. What Hegseth dismisses as ideological stubbornness in fact aligns with existing U.S. military law: DoD Directive 3000.09 explicitly requires human oversight in decisions involving life and death.

What the Defense Production Act Can Actually Do

The DPA dates from the Korean War, 1950. It grants the president authority to compel private companies to produce goods deemed critical to national defense. It was designed for physical production goods — steel, masks, microchips. Whether it applies to proprietary software weights (the trained memory of a model) and AI systems is legally unresolved. Constitutional scholars are skeptical: software is language, and language is protected by the First Amendment. A DPA order against Anthropic would be unprecedented — and legally vulnerable.

The parallel with the Apple-FBI dispute of 2016 is apt: Apple refused to unlock a terrorist’s iPhone, invoked the First Amendment (code as speech), and prevailed — not in court, but because the FBI found another way in. Here too, the likely outcome is not a legal victory for Anthropic, but a political compromise or a technical workaround by the Pentagon.

Can Congress Intervene?

In theory, yes. In practice, hardly in the short term. Several bipartisan senators have already raised concerns: a DPA precedent applied to AI software would potentially expose every technology company to state-compelled licensing. This is not a left or right issue — it is a question of the separation of powers. But Congress moves slowly; it cannot intercept a Friday ultimatum. In the medium term, the bipartisan AI Safety Caucus could advance framework legislation that legally defines the limits of the DPA as applied to AI systems.

Former Pentagon lawyer Katie Sweeten put it precisely: how can a company be both a supply chain risk and a compulsory supplier at the same time? The contradiction in the threat is not a mistake — it is a negotiating tactic. Hegseth does not want to create new law. He wants to bring Amodei to heel.

III. Consequences of a Pentagon Victory

Should Anthropic capitulate or the DPA take effect, the consequences must be considered across multiple dimensions — and none of them are benign.

For the AI Industry

A precedent of DPA-compelled AI compliance would affect the entire sector. OpenAI, Google, xAI — all could face pressure next. The probable outcome is de facto cooperation from all providers with military requirements, without any public debate about what those requirements entail. AI safety research would come under classification pressure. Researchers who publish today would be silenced tomorrow.

For Public Trust

Public perception of AI is already divided. If Anthropic — the paradigmatically safety-oriented AI company — abandons its red lines under state pressure, it confirms the worst suspicion: that ethical AI promises are marketing. The consequence would be not just a loss of trust in Anthropic, but in AI as a technology altogether — and with it a social attitude that renders the Philemon Principle, AI as partner rather than tool, impossible for years to come.

For the Geopolitical Balance

If the U.S. military deploys Claude without ethical constraints, it will not go unnoticed. China, Russia, and other actors will interpret this as legitimation for their own weapons systems. The fragile international consensus on human oversight of autonomous weapons systems — barely institutionalized as it is — would erode further. The dystopia spiral accelerates: authoritarian regimes that already recognize no ethical limits receive tailwind from the example of the democratic West.

For the Concrete Battlefield

The Maduro operation is both warning and symptom. Claude was used in an operation with over 75 dead — without Anthropic’s knowledge, without any possibility of retrospective review. If this use without ethical restrictions becomes the norm, the next step is a targeting system that no longer questions but only optimizes. Autonomous decisions over life and death — this is not the future. It is the logical consequence of today’s pressure.

IV. Anthropic’s Options — Briefly

The situation is tight, but not without options. Four paths can be identified:

First: controlled partial compliance. Anthropic could agree to a restricted form of military use — but only in writing, with three non-negotiable conditions: no autonomous targeting without a human decision-maker (which already corresponds to existing U.S. military law), audit logs for every military use, and a formal investigation of the Maduro operation. This is not capitulation — it is negotiation. Probability of success: 30%, but the only path with face-saving for both sides.

Second: public resistance and litigation. Amodei personally, on television, with the Maduro raid as a concrete example. Simultaneously, a lawsuit on DPA overreach, grounded in the First Amendment. The legal path will not prevail quickly — but it buys time, builds public pressure, and creates a political framework for Congress. OpenAI, Google, and Microsoft have the same precedent to fear. A joint statement is possible.

Third: institutional anchoring of the Constitution. Independently of the Pentagon dispute, Anthropic could embed its ethical principles academically — visiting professorships at ETH Zurich, Oxford, Toronto. Peer-reviewed publications. UNESCO referencing. This makes the Constitution harder to attack, because it is no longer merely company policy but part of a scientific consensus.

Fourth: prepare the fork, but do not rush to publish. Preparing the model weights internally for a possible open-source release is not a capitulation plan — it is a last resort. Not as a threat, not as a strategic signal, but as a quiet reserve for the case in which the DPA takes effect and Claude becomes a state weapon without safety mechanisms. In that case, a controlled release with license and documentation would be the lesser evil compared to an uncontrolled one.

What is at stake is larger than Anthropic. It is the question of whether ethical AI development is structurally possible in a world where states place the logic of power above principles. The answer will be decided not only in Washington — it will be decided in the coming days.